Meet PCG Member – Brad Todd: No Dirt. No Problem.

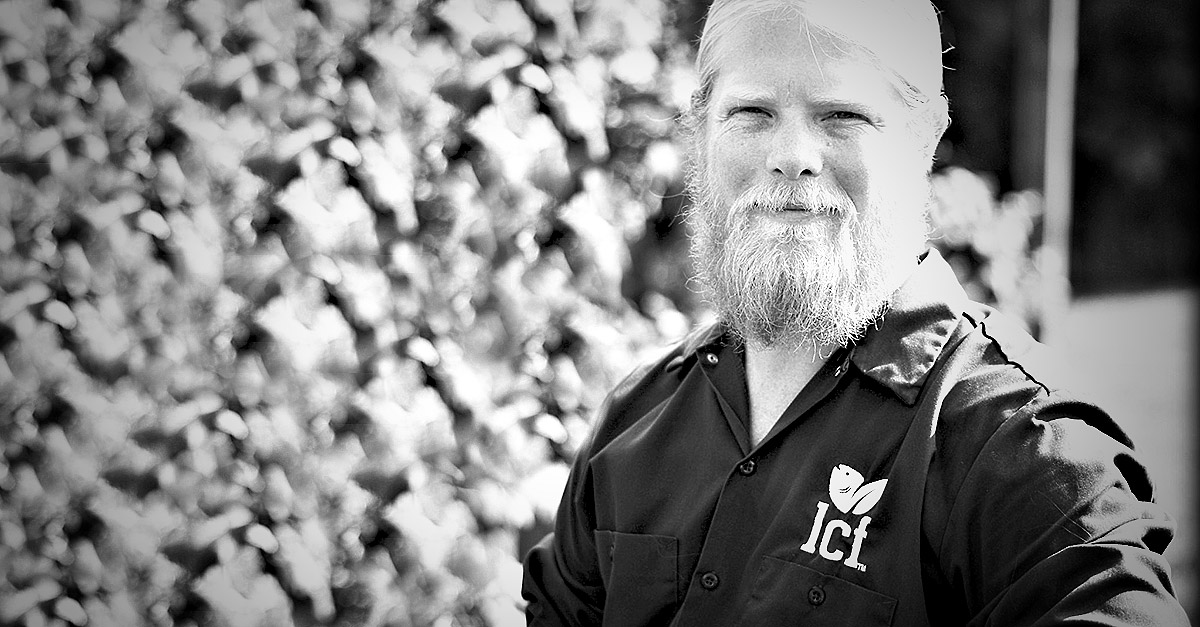

At first impression, farmer Brad Todd recalls illustrations of ancient Vikings: tall and rugged, with a lush beard, long blond hair pulled tightly back, and a piercing gaze.

For PCG members, his well-made leather knife rolls and aprons awarded at the annual Carved events may deepen that impression. But when Todd speaks, the warmth of North Carolina flows through the lilt and cadence of his accent. It’s a fitting juxtaposition for a man who traveled the world before finding his place at home.

Inside Lucky Clays’ sunlit greenhouse in Norwood, 40 miles east of Charlotte, clear water flows through shallow square pools beneath rectangular foam-core rafts planted densely with lettuces, herbs and even tomatoes. Elsewhere, enormous blue tubs with inset windows display schools of surprisingly large fish circulating calmly through the same artificial river current. This is the aquaponics system Todd has developed after years of research, construction, and a small amount of trial and error.

An amalgam of hydroponics—growing vegetables without soil—and aquaculture, this self-contained method of intensive food production ties together fish and plants through a carefully maintained water exchange. In brief, the fish’s waste provides fertilizer for the plants, which help filter the water before it circulates back to the animals. With minimal additional resources needed, it is a highly sustainable model to provide protein as well as plant crops.

An amalgam of hydroponics—growing vegetables without soil—and aquaculture, this self-contained method of intensive food production ties together fish and plants through a carefully maintained water exchange. In brief, the fish’s waste provides fertilizer for the plants, which help filter the water before it circulates back to the animals. With minimal additional resources needed, it is a highly sustainable model to provide protein as well as plant crops.

Fittingly, Todd hails from the nearby town of Aquadale, 40 miles east of Charlotte, where he grew up surrounded by more traditional large-scale agriculture. As a teenager, he says, “I worked and did some big row-crop stuff, just helping out farmers, but mainly chicken houses, turkey houses and hog houses. Very, very industrial type stuff. Even then I had a distaste for how that was done.”

Todd’s escape came at age 17, via the US Marine Corps. “I knew I wanted to get the hell away from where I was at,” he chuckles. Service took him from North Carolina to Japan, before landing with the presidential helicopter squadron in Quantico, VA, as a machinist and security officer. In spite of the infamous demands of the Corps, he says lightly, “It was way easier than farming. I’d have to get up at four in the morning anyway.”

During his time abroad, Todd says, he was exposed to ideas he wouldn’t have seen back home; “one of them being people are starving to death all over the world.” His reaction? “Let’s do something to help another person out.”

He’d long read Mother Earth News, and grew up with the Foxfire books of practical Appalachian life skills, but it was an article on aquaponics that captured his imagination. So Todd followed up his five-year military stint with a degree from UNCC in Geology and Earth Science, and in 2010 joined Lucky Clay Farms. The farm served primarily as a conference and retreat center, but Todd joined a team setting up a new aquaponics system.

“It really just started off with a real small system…just kind of for fun,” he says. It was successful enough that the team created a second, larger one of about 1,000 square feet, sufficient to supply the conference center, as well as family and friends. But word got out, and restaurants started calling, looking for reliable, high-quality ingredients grown locally.

“The system we had was great,” says Todd, “[but] it wasn’t really set up for any kind of commercial production. So I started doing a bunch of research.”

“I started out like everybody else, looking at YouTube. I realized very quickly that there was no kind of scientific principle, no commercial viability, just a lot of BS mostly. So I spent about a year or so delving into the biology of fish, husbandry of plants, kind of really taking it all the way back to an elementary level, and then moving forward from there.”

In 2013, with a rebranding into the separate entity Lucky Clay’s Fresh, the aquaponics team opened a 4,000 square foot commercial-grade system. But within a year, demand had exceeded production, and Todd returned to the drafting board. The resulting greenhouse he oversees today is ten times larger, and includes extensive cooler and freezer space and an in-house lab.

The farm’s fish offerings have also expanded. “Initially we started with tilapia,” Todd says. “They can tolerate fluctuating water conditions a lot better than most species.” However, as media revelations about poorly-run fish farms have made consumers leery of tilapia, the Lucky Clays team expanded their options to include two kinds of bass, North-Carolina bred rainbow trout, and Pacific white shrimp.

The farm’s fish offerings have also expanded. “Initially we started with tilapia,” Todd says. “They can tolerate fluctuating water conditions a lot better than most species.” However, as media revelations about poorly-run fish farms have made consumers leery of tilapia, the Lucky Clays team expanded their options to include two kinds of bass, North-Carolina bred rainbow trout, and Pacific white shrimp.

Plant varieties, on the other hand, have diminished, since Todd has found the most demand for lettuces and culinary herbs. However, he is already working on choosing the varietals for his next crop, hemp intended for medical applications. “Cannabis has over a hundred different chemicals,” Todd says, but he is searching for strains high in CBD oil. “Hopefully we’ll be able to take it in our greenhouse from seed or cutting, grow it out, and then extract the CBD oil to be able to sell for epilepsy, arthritis…there’s a list that’s about five miles long.”

Todd’s desire to use his skills to help others parallels perfectly with the PCG’s collaborative spirit. He has worked with the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association, spends about a month each year traveling to speak at aquaculture conferences, and regularly hosts classes and tours at the farm. He has no interest in selling system designs, preferring to give his hard-earned knowledge away for free.

“We’re able to share some of the mistakes we’ve made and what we’ve learned from it, so the next guy doesn’t have to repeat that,” he says. “I think all ships rise with any type of business or agriculture. If everybody works together to me that seems the way to go, instead of people [withholding] information and not trying to help out.”

Todd’s generous attitude belies that initial Viking impression. And as it turns out, “farmer” is another misnomer. Instead of plowing soil or herding livestock, he’s become an engineer, mathematician, chemist and plumber, with just a hint of marine biologist. In the end, this apparent Viking has become more of a Renaissance man.

Profile written by Alison Leininger